In this episode we take a deep dive into PMA’s upcoming production of Orlando's Gift written and directed by Professor David Feldshuh. On rare occasion we take a different approach with an episode, remove the standard back and forth conversation, and capture a poetic narrative from our guest. Please take a moment to sit back, relax, and enjoy the words of David Feldshuh as he describes his upcoming production from its inception to present.

Click HERE to see more episodes.

Transcript

00:00 Music.

Chris Christensen 00:11

Hello. I'm Christopher Christensen. Welcome to Episode 62 of the PMA podcast. In this episode, we take a deep dive into PMA's upcoming production of Orlando's Gift written and directed by Professor David Feldshuh. On rare occasion, we take a different approach with an episode, remove the standard back and forth conversation and capture a poetic narrative from our guest. Please take a moment to sit back, relax and enjoy the words of David Feldshuh as he describes his upcoming production from its inception to present.

David Feldshuh 00:43

How this process came to be. Well, that's a story in itself. A little less than a year ago, one or perhaps two or three of my superb directing students came to me and said, or asked, "Will you direct us on something?" And I told them that I like to do plays with lots of people in them. So the last play I did here at Cornell was the Awakening of Spring that probably had about 23 people in it. And as I think back on it, the largest one I've done was Bernstein's opera Mass, which had 138 people in it. So I wasn't expecting quite that, but I was probably trying to really discourage this student, or these students, because I wasn't sure that we really had the the people who would be interested in doing a project at the level that I would like to do it and with the kind of dedication that would be required. And they came back to me again. And yet, they came back to me again. And finally, I said, 'Well, if you can show me that you have a significant number of students that want to participate in this project, then we'll find something.' So sure enough, I start getting emails, and after about 11, and this was a group that knew each other, and these were, for the most part, advanced students in the theater area. I wrote back to them and said, Are you sure you want to do this? Because this might be challenging. And they wrote back, every one of them by email. And then I wrote back again. I was still skeptical. Well, after about the third time, my skepticism slowly oozed away. And I then realized that I was trapped, so I was going to direct. And then the question became obvious, I was going to direct this group of students, 11 students, what were you going to do? And my basic metric was I wanted to do something that would challenge the students, excite them and keep them involved, but I also wanted to do something that challenged me, excited me and kept me involved.

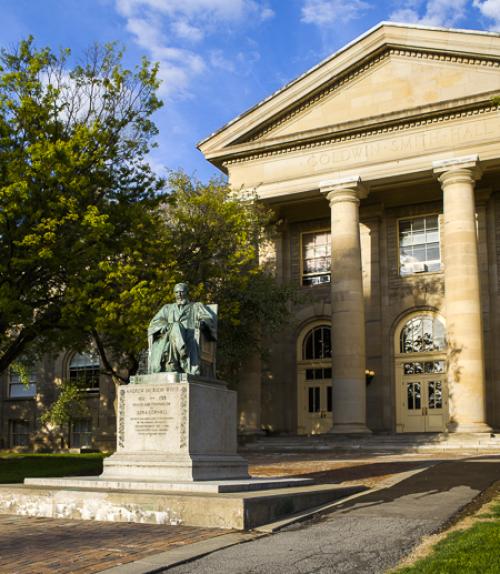

So I went through a number of different permutations and thinking about different plays and realistic plays, and I decided I didn't want to do the umpteenth production of this particular play Shakespeare was has always been of interest to me, but I finally arrived at a moment's notice in a peculiar way that's resonant with the ultimate final product. This moment of kind of either insight or sparking or intuition or brainstorm. I went back 50 years because almost 50 years ago, not quite I was in Minneapolis, and I was a young professional director and actor with the Guthrie Theater. And I was working on a project--asked to work on a project with the Illusion Theater, which is a professional theater that focuses primarily on new plays and developing new plays, as well as important social content. They're one of the first theaters ever, way back in the 70s, to do work that focused on sexual abuse of children and preventing it. And I have-- very friendly with the people who run this as a matter of fact, they were previous students of mine, and they asked me to work on a book that they wanted to adapt. And the name of that book was Orlando by Virginia Woolf. And I didn't know the book.

I can tell you, it was a hot summer sometime around 1976 and we sat in a second floor of a converted factory without any air conditioning, and we read through every page and every word of that book, and we improvised what we thought was improvisable, if that's a word which it probably isn't. And we completed a production, and that production was brought back. And for some reason, that production came back into my mind, and I knew I wasn't interested in replicating that production or even using that script, which I didn't write. Since that time, I've adapted a number of scripts, including whatever here at Cornell Antigone and the Awakening of Spring and Little Women. And outside of Cornell, a number of other different scripts. And I've had some original scripts that are not adaptations, such as Miss Ever's Boys and Dancing With Giants that was also performed professionally in 2018 and I thought, 'No, I think I would like to write this one myself.' And I have no idea why I said that, except that I thought this would be a challenge and this would keep me interested. So now we're somewhere around December or January.

So I say this to the students, and they're still on board. Well, they're still on board, I'm still on board, and I start this process of adaptation, and that's a whole story in itself. But I think the bottom line of the story is, I really re-fell in love with Virginia Woolf, even more so than 45 years ago, just the bravura use of language, the poetry, the stream of consciousness, and in Orlando in particular, the wit. It is a very, very witty book, the richness of characterizations. And then I started this process of adaptation, and I wanted to do, I knew a production that was in the realm of story theater, meaning highly physical, fantastical, not realistic, involving different elements, like accents, the ability to speak language and deal with that, that wit that requires a certain just dexterity of handling words and vocal variety, using group movement, All the things that I thought, and still think, would be useful skill sets for the students to experience. And the wonderful thing about this story is that it allows for all of this. It's a wide palette, and I can talk about the story in a moment, but it's Virginia Woolf's comedy. She describes it as a romp.

She describes it as "half laughing, half serious with great splashes of exaggeration." And that is more or less the raison d'etre. The motto of our production is, is to take all those aspects of theater that define what it means both to be theater and a theater actor, that craft and in a way, demand that those things be used in order to bring this incredible, wide ranging romp, giddy romp. Virginia Woolf said, I can't believe this is any good. I'm having too much fun. It's a writer's holiday, etc, etc. Bring this to life. So to continue, Orlando is the story of a young man who lives at least 300 years, maybe 400 maybe forever. It begins in Elizabethan times and goes until the 20th century, specifically the 1920s when the book was published. And it's the story of a young man in search of his identity. And what Woolf is stating or saying is that we have many identities. And the simplest way of understanding this or thinking about this is you might have an identity as a husband and also a father, but also a teacher, but also a grandfather. You may have an identity as a fan of music or of sports or whatever, and each one, when you really start to think about it, may have their own costume, may have their own way of speaking, may have their own sense of community. So that was one of the things that she explored. And Orlando as he goes through time, first discovers that time is fluid, that a second may be a week, a week, maybe a year, 100 years, maybe a day. So everything is fluid. Identity is fluid.

So. And Orlando wants to be a poet, and so he wants to write, and he feels that I have to be able to feel deeply if I want to be a poet. And so early on in his journey, he experiences love and heartbreak with Sasha, the Russian princess. He becomes a favorite of Queen Elizabeth, and she is taken with his vitality and his youth. And then he experiences what it's like to write and to be criticized and to be broken because of it. And throughout all this, he meets people that do have fluid identities. But he also looks at the questions of, what does it take to write, what does it take to create? What does it take to think of a word or a sentence or a book? And these, of course, are questions that Virginia Woolf is asking herself. And Orlando goes on, and somewhere, while he's 30, even though he's lived for a couple of 100 years, he becomes a woman. And so there's this gender change, and then he experiences life as a woman, and all the implications of that. So this world that Virginia Woolf has created, as I said, is a world of the fantastical.

You don't know what's coming next. It's a comedic world. But there's another story I felt in Orlando that I was taken with, that I wanted to tell, and that's the story of Virginia Woolf herself. Virginia Woolf loved language. I believe she was an incredible writer. She was a feminist, perhaps before that, certainly before that word means exactly the same thing as it means today. For example, She said that when you look back, when you think about books written by anonymous, almost all of those anonymous are women. And she was in love with Vita Sackville-West, who lost her family home, because if you've ever watched Downton Abbey, a woman could not inherit it would have to go to a male heir. In this case, it was to a cousin. And she was also a writer. She took writing extremely seriously, even though she was among a group of very witty people. Unfortunately, she also suffered. She also suffered from mental illness, and the various ways that you would characterize her mental illness. One way is Psychotic Neurasthenia, that's what they called it in those days. And as a physician myself, practicing emergency medicine for 40 years, I was also taken with the very unfortunate fact that Virginia Woolf had multiple attempts to take her own life, to commit suicide and to embrace -poetically-death, and she succeeded in committing suicide in 1941 unfortunately, by putting stones in her pocket and walking into the River Ouse in England. And I looked at the number of times that she tried to commit suicide, and she tried to commit suicide, roughly the ones that at least I could find and read about in, say, 1915 and then in 1935 and then of 1941 where she succeeded, but she didn't, as far as I could tell, try to commit suicide in the 1920s which is when she wrote Orlando, also when she was in love. And by the way, this book has been described as the longest love letter in English literature to her, her partner, her love interest, Vita Sackville-West. And my thinking was perhaps half as a person who enjoys the vitality of physical and verbal theater and part as an emergency physician is was the fact of Virginia Woolf writing this book, the lifeline that helped her not to commit suicide, Not to try to commit suicide, in the 1920s so the very-- my basic premise. My basic premise was, what if Virginia Woolf had gone to the River Ouse earlier than 1941 and tried to put.

Stones in her pocket and walked in to the River Ouse, and as she was drowning and she became more hypoxic, that is, she lost oxygen to her brain. She imagines she hallucinated the story of Orlando, and she falls into this story, and she has a relationship with this figure of Orlando, male Orlando, and then a woman Orlando, and she brings this figure of Orlando to life, but Orlando also gives her the realization that she can write. Imagining the story is Orlando's gift to her, and the story is the gift of aliveness to Orlando. So it's a Orlando's Gift is a way of looking at a two way communication. And the other thing I found out about Virginia Woolf, among many things, was her realization that her madness, or certainly the voices in her head, were important to her creativity. So it's not as if she simply dismissed them. There was something about madness and creativity that stirred her imagination, and yet there were certain things that dragged her down, that were voices that spoke with her. So if you think that, if you use as a frame, Virginia Woolf walks into the River Ouse, and then imagines this story, and falls into this story and becomes integrated with these various fantastical characters, and has a love relationship with this character of Orlando, when I say a love relationship, I mean a deep, sustaining, nurturing love relationship, that relationship needs to unlock something in her madness that is causing her to be self destructive. And as I did more and more research, I realized, of course, that there was something there, and that is that Virginia Woolf was sexually abused by her step brothers as a child and as a teenager, and so the unlocking of this secret becomes a way for her to gain, regain her faith in her own ability to write and her own ability and willingness to live, and that is the story. Now, what's interesting about this story is you have a high, comedic romp, a giddy, fantastical story, and we've added some elements to it. For example, Shakespeare appears and his sister appears Judith, and the reason his sister appears is because Virginia Woolf mentions, what would it be like if Shakespeare had a sister, not in Orlando, but in another book. And so I thought, all right, let's see what happens if Shakespeare does have a sister. And it turns out that Shakespeare's sister has written most of the things, and Shakespeare himself simply had very good penmanship, so he wrote everything down.

And so there's this mentorship relationship in this fantastical world that that Virginia Woolf moves through, but there's also this pull, this pull to take her own life. So how do you take this fantastical comedy and thread the pain, the suffering, the madness, the creativity, the sense of the willingness to experience multiple selves that Virginia Woolf evidenced in her real life, and create a single play from that. And that was the challenge, and that's the challenge that my cast and I are trying to meet. So now you have a character, a lead character, Virginia Woolf, who is actually writing the book Orlando, as the play unfolds. So she has a very particular relationship with these voices in her head. And as I said there are voices that go back to her ugly secrets when she was abused as child. There are other voices that are creative voices, and those voices we've chosen to call words because she was in love with language, so you have a group of actors who are these words, and then these words, as in writing a book, become sentences, and then paragraphs and then characters. So they come out of this chorus, they become a character, and then they go back into this chorus of words. And of course, you think of Hamlet, words, words, words, and these words are witty, they're nimble, they're playful, they're wry, they're satirical. They really leaven the whole process. They also become everything that you might imagine from dogs to emotions like jealousy or lust. How are you going to show that physically? That's part of the kind of challenge that this kind of production, this highly physical production, presents to actors.

How do you deal with the rhythm and the tempo of language? How do you deal with multiple characterizations? So we have 10 actors playing 41 roles, and obviously that takes skill and discipline and determination and practice, because when Orlando or Virginia Woolf talks about too many selves to count. Some say 2052 she says, we're going to be showing a lot of those selves. And the journey that Orlando has, and Orlando himself actually is played by two men and one woman. So Orlando, he/ her, also changes. Has multiple identities, both in terms of gender as well as in terms of profession. As a production, when you have 41 characters played by 10 actors, simply in terms of costume, what you want to do is start with something that is basic, not necessarily neutral, but something that allows everyone to participate in the same sense of community, and then you can add or take away bits and pieces or something more than that. So in this production, there are numerous costume changes, and the set also is open to the imagination. I think part of this kind of theater has to do with igniting the imagination of the audience, and the way you do that is either with the language, with the visualization, with the tableau, with the combination of music and sound and text, and so they you create part of it, and frequently the audience finishes it in their imagination. So you want a set that's also open and allows for that. And on this in this set, we have four pole ladders. So a pole ladder is just like just as it says. It's a pole with cross bars that go up and that allows numerous kinds of visualizations.

You have huge sail cloth across the back that come come up and down in various permutations. So the set is also fluid. Everything is fluid. Time is fluid. Obviously light and sound can be instantaneous. You can create a picture. You can hold that picture. You can have actors come out from that picture. Because, again, the world is the world in part of Alice in Wonderland. I do want to say one thing about this cast that got me into this. So I did a production of this, as I said, about 45 years ago. And I've been at Cornell for 40 years, and I've been a professional director for more than that time, so I've worked on a lot of productions as a director, and a number that I've of plays that I've also written and directed, but this cast has had to be willing to go on a journey to some sort of unknown place. This is a completely new play. Never been done before. They will be the first people on earth to say the words of this play. Now, some of those words are Virginia Woolf's words, but to say the words of this play in front of an audience, and so there's an incredible sense of discovery, but there's also a sense of trial and error. So they have had to be willing to attend, to pay attention, to be determined, to have perseverance, but above all, I think, to have a sense of community. And laughter, to me, laughter in rehearsal is really important. It's not just a release, it's a sign that we're in this together, and we're still making a go of it. And this has been a remarkable cast. Some people ask, Well, what do you expect to come from this play? I have absolutely no idea the future of any play, and I've written a number of them, is fragile and it's also unknown.

I've had successes where I thought I would never would, and I've had failures where I thought, wow, that's going to be really big. And you can't tell that's what I've learned over the years, but one thing I will say is that the present moment the present process, although it was brutal writing this, which I did for about six months, draft after draft after draft, professional readings, multiple professional readings, At The Cherry then at the Illusion Theater in Minneapolis, change people suggesting changes, all of these things that are part and parcel of developing a new script and then beginning in a play that has 15 scenes, and goodness knows how many scene changes, none of which you have to wait for. Every scene change, like in Shakespeare, goes on and the text goes on. So the whole thing is fluid. I'd say each act is about 55 minutes to 60 minutes. And there's two acts, and all of these things, which are just a heavy duty dose of trying to put something together has really just been fun. I tell my students that my secret when I was a young director was that I didn't want anybody to know that I would be willing to do this for free, because I was getting paid for it and doing this production, I both feel the same way, and it reminds me of why I said that 50 years ago.